Culture in the Christian Worldview: Part II

Part II: The Current State of Culture

This

is Part II in a three-part series on Culture in the Christian Worldview.

Click here to read Part I.

Cast

out of Eden

The Christian worldview would be incomplete

if it didn’t incorporate the Fall. After all, we are not still living in Eden.

To understand the current state of culture, then, we must consider Adam and

Eve’s rebellion in Genesis 3. Adam and Eve reject God’s order in favour of

their own constructions of good and evil. They sin and introduce shame and

barriers in their relationship between each other and with God. This is

symbolized in the first thing man makes apart from God:

‘Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked. And they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves loincloths.’ (Gen. 3:7)

This is a paltry and feeble construction,

but it demonstrates how we may turn to culture (the things we’ve made) to put

distance between each other and God. This separation caused by sin is

consolidated as God casts Adam and Eve from Eden:

‘Then the LORD God said, “Behold, the man has become like one of us in knowing good and evil. Now, lest he reach out his hand and take also of the tree of life and eat, and live forever—” therefore the LORD God sent him out from the garden of Eden to work the ground from which he was taken. He drove out the man, and at the east of the garden of Eden he placed the cherubim and a flaming sword that turned every way to guard the way to the tree of life.’ (Gen. 3:22-24)

The flaming sword prevents man’s return to

Eden, the world holding the tree of life. Thus, the eastward trajectory of mankind

begins. We now inhabit a cursed world, full of toil, pain and thorns, and

cannot return to Eden, the place of origin, divine order and perfect unity with

God. Yet we still yearn to ‘reach out his hand’ and eat of its fruit.

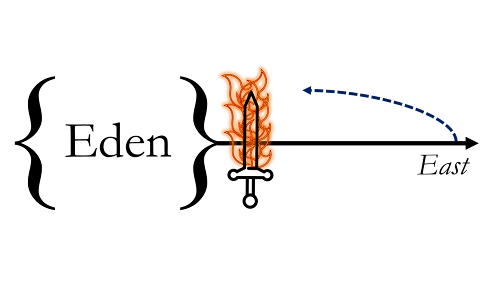

This desire to return to Eden is the framework with which I propose we should approach literature. All artistic endeavours are examples of man acting on his God-given instinct to be creative, an expression of our desire to return to Eden. Culture tries to chart a course there by rehearsing the values we remember from our time there. This cultural trajectory could be represented like this:

There are four features to this:- Eden: This garden represents life before the Fall; beauty, perfection and unimpeded relationship with God and reality. We are desperate to return to Eden or somehow recreate it.

- The Trajectory East: Adam and Eve were banished from Eden in this direction, and as there is no going back, this is the path to which we are bound; away from God.

- The Flaming Sword: In God’s providence, he has placed a flaming sword at the eastern end of Eden. This is an impenetrable barrier preventing our return to Eden; we have gone past the point of no return.

- Culture: The blue arrow, trying to return to Eden and bridge the gap caused by our rebellion.

Despite our fallen nature, Eden draws our cultural attention because of its goodness. We find solace and meaning in the characteristics of Eden, and depend on these (often without realizing) to give our cultural endeavours emotional weight. Such characteristics include:

- Harmony (with God, with fellow man and nature. Also in rationality, musicality, etc.)

- Love/intimacy (including sexuality)

- Justice/order

- Goodness/beauty

- Truth/honesty

- Potential/opportunity/innovation

- Innocence/purity

- Light

Literature recognizes and relies on many and more of these good things, to varying success. It highlights these values both by portraying these values and by focusing on the gulf between them and society, e.g.:

- Pain/suffering

- Death

- Discord/chaos

- Injustice

- Evil/horror

- Hate

- Lies

- Darkness

These are inversions of Eden’s values, and

just like the thorns brought about in Genesis 3:18, they serve as a reminder of

how fallen Creation is. It is part of God’s common grace that things like

injustice, lies and the nonsensical - in the world or in culture - does not sit

well with us. C. S. Lewis captures this function in The Problem of Pain:

‘pain insists upon being attended to. God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts in our pain: it is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world’. (C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain (Collins, 2001), p. 91

Colossians 1:16 reminds us that ‘all things

were created through him and for him’; ‘him’ being Jesus Christ, ὁ λόγος. Not only did Jesus create and sustain everything,

but he is also the endpoint (or telos)

of all things. It is inevitable then that our cultural expressions should reflect

this connecting thread, the impulse to strain after perfection, beauty or some

higher value, because all of the raw material we can draw from belongs and

testifies to Christ. Culture resonates with us, as, with varying clarity, it

displays fundamental truths about the human condition.

A

Godless Eden

Every attempt to re-enter Eden is

unsuccessful, for two reasons. Firstly, because the flaming sword prevents our

return, and secondly, because what we are aiming for does not exist; an Eden

without God. Romans 3:10-12 reads:

‘“None is righteous, no, not one; no one understands; no one seeks for God. All have turned aside; together they have become worthless; no one does good, not even one.”’

The first sin of Adam and Eve was to reject

God, in an attempt to become like him. The Eden they wanted was one without

God, and that is the same type of Eden mankind is looking for. The Romantic poets, for example,

were obsessed with locating ‘the Sublime’ - a paradise, but without any divine

presence. They always fail, because they sought something that does not exist.

Their despair and frustration at this is further evidence of the futility of

fallen man.

One of the words translated as ‘sin’ in the

Bible captures this element well: ἁμαρτία (‘hamartia’). An archery term,

hamartia means to ‘miss the mark’; to aim in the wrong direction. Our sin

prevents us from clearly seeing Eden, and so we chase after a distorted vision

of it, all the while heading even further east.

We must be careful to note that whilst

culture looks for a sort of Godless Eden, some examples are definite attempts

to accelerate eastwards. H. R. Rookmaaker’s book The Creative Gift (see Resources) describes a category of culture

as ‘in the line of Cain’. Cain’s descendants in Genesis 4:17-24 answer the

God-given desire to create, but this trajectory is one that culminates in the

perverse song of Lamech in 4:23-24, which celebrates his bloodthirsty

vengeance. Culture that glorifies evil like this belongs to this tradition,

repurposing God’s creative gifts to ungodly ends.

Glimpsing Eden

The world is bound on this eastward

trajectory. But God in his mercy does not leave mankind without some comfort or

goodness; he replaces Adam and Eve’s primitive fig leaves with ‘garments of

skins’ (Gen. 3:21) ahead of their exile from Eden. This typifies the idea of

‘common grace’, that God protects us from the full consequences of our sinful

nature. Paul explains this in Acts 14:

‘“In past generations [God] allowed all the nations to walk in their own ways. Yet he did not leave himself without witness, for he did good by giving you rains from heaven and fruitful seasons, satisfying your hearts with food and gladness.”’ (Acts 14:16-17)

Not only does God meet the material needs

of the rebellious world with rain and seasons, but he allows man to enjoy

‘goodness’ in his heart. In spite of our sin, God has not removed our eyes for goodness

or ‘gladness’. Jesus also underscores this:

‘“Or which one of you, if his son asks him for bread, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for a fish, will give him a serpent? If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father who is in heaven give good things to those who ask him!”’ (Matt. 7:9-11)

Jesus illustrates God’s generosity by pointing

out that even ‘you... who are evil, know how to give good gifts’. Despite our

corruption and wickedness, God still gives us the capacity to recognize

goodness and do good to each other. We still harbour some desire for good

things and the ability to recognize them, and in this sense, we can still

glimpse something of Eden.

Culture testifies to this common grace,

acting as a barometer for the good and evil desires of man’s heart. By

discerning what we watch and read, we can learn something of our world’s

tensions and values. The central tension, perhaps, is between celebrating the

good and suppressing the truth; between our trajectory east and our collective

yearning to return to Eden. Ecclesiastes 3:11 affirms this central tension:

‘He has made everything beautiful in its time. Also, he has put eternity into man’s heart, yet so that he cannot find out what God has done from the beginning to the end.’

God has placed eternity in our hearts,

planting in us the desire of wanting eternity and celebrating good things. The

closest thing to paradise that we can conceptualize is Eden. However, like

Tantalus, Eden is always beyond our cultural reach. This tension and limitation

energizes the literature that we read.

Reading culture through this lens enables us to spot the insufficiencies and triumphs of art, and the predicament our culture is currently in. What values does it affirm? Where does it fall short of the truth? God in his mercy has placed us, as speaking creatures in a speaking world. Let’s listen to it carefully. Part III considers how and why we might do this.

Click here to read Part III: The Christian and Culture.

Comments

Post a Comment